If your child has been diagnosed with a congenital heart defect, it means that your child was born with a problem in the structure of the heart.

If your child has been diagnosed with a congenital heart defect, it means that your child was born with a problem in the structure of the heart.

Some congenital heart defects don't need treatment, while other are more complex and may require treatments and occasionally several surgeries performed over a period of several years.

How the heart works

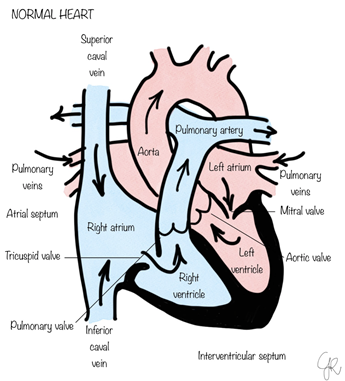

Chambers and valves of the heart

Chambers and valves of the heart

The heart is the muscle that is responsible to pump blood around our body.

It is divided into four hollow chambers, two on the right, the Right Atrium (RA) and the Right Ventricle (RV) and two on the left, the Left Atrium (LA) and the Left Ventricle (LV).

The RA and the LA are the top chambers also known as collecting chambers, the RV and the LV are the lower chambers, known as the pumping chambers.

To pump blood throughout the body, the heart uses its left and right sides for different tasks.

The right side of the heart pumps blood to the lungs through vessels called pulmonary arteries. In the lungs, blood picks up oxygen then returns to the heart's left side through the pulmonary veins. The left side of the heart then pumps the blood through the aorta and out to the rest of the body.

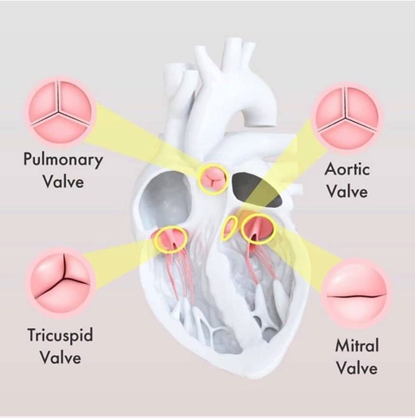

The heart has for valves, depicted in the below pictures. The heart valves connect the collecting chambers to the pumping chambers, and the pumping chambers to the outlet arteries.

The heart valve have the ability to allow blood to flow forward when in open position but to block blood to flow backward when in close position.

How heart defects develop

During the first six weeks of pregnancy, the heart begins taking shape and to develop both the heart chambers and the major blood vessels.

It's at this point in your baby's development that heart defects may begin to develop.

Most of these defects develop as genetics, certain medical conditions, some medications and environmental factors, such as smoking and alcohol, may play a role.

CHD happens in about 8 babies out of every 1,000 (0.8%).

Types of heart defects

There are many different types of congenital heart defects, falling mainly into these categories:

Holes in the heart

Holes can form due to a lack of development in the muscle between heart chambers and/or between major blood vessels (arteries and veins) reaching or leaving the heart.

In normal circumstances, a hole in the heart allows oxygen enriched blood to flows from the left side of the heart to the right side mixing, resulting in too much blood flow to the lungs. In certain situations, the oxygen poor blood flows from right side of the heart to the left mixing with oxygen-rich blood, resulting in less oxygen being carried to your child's body. This lack of sufficient oxygen in the blood can cause your child's skin or fingernails or lips to appear blue.

A ventricular septal defect is a hole in the wall between the right and left pumping chambers on the lower half of the heart (ventricles). An atrial septal defect occurs when there's a hole between the upper heart chambers (atria).

An atrioventricular septal (canal) defect is a condition that causes a hole in the centre of the heart in both the collecting and pumping chambers.

A Ductus Arteriosus (DA or Ductus) is a connection between the pulmonary artery (containing deoxygenated blood) and the aorta (containing oxygenated blood) which is normally present during foetal life and normally closed within the first 24-48 hours. If it fails to close blood will flow from the pulmonary artery to the aorta and it is called Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA).

Obstructed blood flow

When blood vessels or heart valves are narrow because of a heart or valve defect, the heart must work harder to pump blood through them. This condition may leads to enlarging of the heart and thickening of the heart muscle. Examples of these defects are pulmonary valve stenosis or aortic valve stenosis.

Abnormal blood vessels

Several congenital heart defects happen when blood vessels going to and from the heart don't form properly, or they don’t connect to the heart correctly.

In transposition of the great arteries the pulmonary artery and the aorta are coming out the wrong pumping chamber and blood struggle to mix, so that an intervention is needed soon after birth to open up a communication between the collecting chambers so that blood mixes. This is to allow the newborns to settle while planning for more definitive surgery in the following weeks.

A condition called coarctation of the aorta happens when the main blood vessel supplying blood to the body is narrow and the lower body does not receive enough blood.

In anomalous pulmonary venous connection the blood vessels from the lungs attach to wrong collecting chambers and oxygenated blood if pumped back to the lungs, instead of the body.

Heart valve abnormalities

If a heart valve does not develop fully, it might not open and close correctly, and blood struggles to flow smoothly through it or it leaks back.

One example is Ebstein's anomaly where the tricuspid valve, between the right atrium and the right ventricle, is malformed and often leaks.

Another example is pulmonary atresia, in which the pulmonary valve is missing between the right pumping chamber and the lungs artery and blood cannot flow to the lungs.

An underdeveloped heart

Sometimes, part of the heart muscle fails to fully develop, like in hypoplastic left heart syndrome, where the left pumping chamber hasn't developed enough to pump enough oxygenated blood to the body.

A combination of defects

Some infants are born with several heart defects. Tetralogy of Fallot is one of the most common where a hole in the heart between the heart's ventricles is associated with a narrowed passage between the right ventricle and pulmonary artery.

Risk factors

Most of the causes of congenital heart defects are unknown. However, we do know that certain environmental and genetic risk factors may play a role. They include:

- Rubella (German measles). Having rubella during pregnancy can cause problems in your baby's heart development.

- Diabetes. The risk of developing a congenital heart disease if mum is known diabetic can be reduced by controlling blood sugar level before attempting to conceive and during pregnancy.

- Medications. Certain medications taken during pregnancy may cause birth defects, including congenital heart defects. Some medications are known to increase the risk of congenital heart defects, like angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, statins.

- Drinking alcohol during pregnancy. It is advisable to avoid alcohol consumption during pregnancy because it increases the risk of congenital heart defects.

- Smoking. Likewise, smoking during pregnancy increases the likelihood of a congenital heart defect in the baby.

- Heredity. Genetic testing can detect disorders during foetal development especially in families where one of the parents had a congenital cardiac disease. If you already have a child with a congenital heart defect, there is a small chance, higher than normal, that your next child will have one.

Complications

Some potential complications that can occur with a congenital heart defect include:

- Congestive heart failure. This serious complication may develop in babies who have a significant heart defect. Signs of congestive heart failure include rapid breathing, often with gasping breaths, and poor weight gain.

- Slower growth and development. Children with congenital heart defects often develop and grow more slowly than do children who don't have heart defects. They may be smaller than other children of the same age and, if the nervous system has been affected, may learn to walk and talk later than other children.

- Heart rhythm problems. Heart rhythm problems can be caused by a congenital heart defect or from scarring that forms after surgery to correct a congenital heart defect.

- Cyanosis. If your child's heart defect causes oxygen-poor blood to mix with oxygen-rich blood in his or her heart, your child may develop a greyish-blue skin colour, a condition called cyanosis.

- Stroke. Although uncommon, some children with congenital heart defects are at increased risk of stroke due to blood clots traveling through a hole in the heart and on to the brain.

- Emotional issues. Some children with congenital heart defects may feel insecure or develop emotional problems because of their size, activity restrictions or learning difficulties.

- A need for lifelong follow-up. Children who have heart defects should be mindful of their heart problems their entire lives, as their defect could lead to an increased risk of heart tissue infection (endocarditis), heart failure or heart valve problems. Most children with congenital heart defects will need to be seen regularly by a cardiologist throughout life.

Tests to diagnose a congenital heart defect

Non-invasive tests

Foetal echocardiogram (Foetal Echo)

This scan allows to see if your child has a heart defect before is born, allowing your doctor and you to better plan treatment, if needed. In this test, ultrasound is used to get picture of your baby's heart while he or she is still in the womb.

Echocardiogram (Echo)

After your child is born, doctors may use a regular echocardiogram to diagnose or confirm the presence of a congenital heart defect.

It is non-invasive test performed by the bedside or in the outpatient clinic; the doctor performs an ultrasound to produce images of the heart to see your child's heart while moving and can detect abnormal flows of blood through chambers or valves.

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

This test is able to records the electrical activity of the heart and to diagnose rhythm problems. Small dots are positioned around the body and connected to a computer and printer to show waves that indicate how your child's heart is beating.

Chest X-ray (CXR)

A chest X-ray could show the shape of the heart, or if the lungs have extra fluid in them which could represent signs of heart failure.

Pulse oximetry (SAT)

This test measures how much oxygen (Saturation) is in your child's blood. A sensor is positioned over one of your child's finger or toes to record the amount of oxygen in your child's blood.

Invasive Tests (or requiring general anaesthesia in small children)

Cardiac catheterization

In order to perform this test your child is put to sleep with an anaesthesia and a specialist cardiologist trained in performing such test insert a thin, flexible tube (catheter) into a blood vessel via your baby's groin and guided into the heart.

Catheterization is sometimes necessary because it may give your a much more detailed view of your child's heart defect than an echocardiogram and allows to directly measure pressures and saturation within the heart. Moreover, during the catheterisation, some treatment procedures can be performed to improve your child heart condition.

Computerised Tomography (CT)

A scan which uses X-rays and a computer to create detailed images of the inside of the body, in particular the heart, lungs and major arteries and veins. CT scans are nowadays fast and require lower X-rays than previously.

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

This type of imaging is becoming increasingly used to diagnose and evaluate congenital heart defects in adolescents and adults. Newer MRI technology provides faster imaging and higher resolution than other methods, such as echocardiography.

Treatments available

As pointed out before, many congenital heart defects may have no long-term effect on your child's health. In some instances, such defects can safely go untreated. Certain defects, such as small holes, may even correct themselves as your child ages.

Some heart defects, however, are serious and require treatment soon after they're found. Depending on the type of heart defect your child has, doctors treat congenital heart defects with:

Procedures using catheterization

Some children and adults now have their congenital heart defects repaired using catheterization techniques, which allow the repair to be done without surgery. Catheter procedures can often be used, in particular in older children and adult patients, to close holes or to enlarge areas of narrowing.

Open-heart surgery

Depending on your child's condition, they may need surgery to repair the defect. Many congenital heart defects are corrected using open-heart surgery. In open-heart surgery, the chest has to be opened. Most of the operations within the heart or the great arteries and veins are performed with the use of the heart-lung machine (Cardio Pulmonary Bypass CPB), which allows surgeons to operate in a bloodless and motionless field. For more information on individual procedures, see the Procedures area of this website.

Heart transplant and heart support

If a serious heart defect or a heart condition like myocarditis can't be repaired or any other treatment cannot be offered or it is not available, a heart transplant may be an option. Unfortunately, in the UK the rate of heart transplantation has been low consistently in the last 2 decades. This is due to lack of donors. In parallel to heart transplantation a great deal of improvement has been achieved in the field of mechanical support where an “artificial heart” has been engineered and developed to allow temporary and longer term support of heart support.

Medications

Some mild congenital heart defects, especially when diagnosed in childhood and adulthood, can be treated with medications that help the heart work more efficiently.

Sometimes, a combination of treatments is necessary. In addition, some catheter or surgical procedures have to be done in steps, over a period of years. Others may need to be repeated as a child grows.

Long-term treatment

Some children with congenital heart defects require multiple procedures and surgeries throughout life. Although the outcomes for children with heart defects have improved dramatically, most people, except those with very simple defects, will require ongoing care, even after corrective surgery.

Lifelong monitoring and treatment

Even if your child has surgery to treat a heart defect, your child's condition will need to be monitored for the rest of his or her life by specialist team

Initially, your child with a congenital heart defect will be monitored and have regular follow-up appointments with a pediatric cardiologist. As your child grows older, care will transition to an Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ACHD) cardiologist, who can monitor his or her condition over time. A congenital heart defect can affect your child's adult life, as it can contribute to other health problems. Adults who have congenital heart defects may need other treatments for their condition.

As your child ages, it's important to remind him or her of the heart condition that was corrected and the need for ongoing, lifelong care by doctors experienced in evaluating and treating congenital heart disease. Encourage your child to keep his or her doctor informed about the heart defect and the procedures performed to treat the problem.

Exercise restrictions

Parents of children with congenital heart defects may worry about the risks undertaking regular exercise or play sports, even after successful treatment. Although some children might be limited in the amount or type of exercise, many can participate in normal or near-normal sport activity.

Infection prevention

Depending on the type of congenital heart defect your child had, and the surgery used to correct it, your child may need to take extra steps to prevent infection.

Sometimes, a congenital heart defect can increase the risk of infections — either in the lining of the heart or heart valves (infective endocarditis). Because of this risk, your child may need to take antibiotics to prevent infection before additional surgeries or other procedures like dental of aesthetic procedures.

Children who are most likely to have a higher risk of infection include those whose defect was repaired with a prosthetic material or device, such as an artificial heart valve.

Ask your child's cardiologist if preventive antibiotics are necessary for your child.